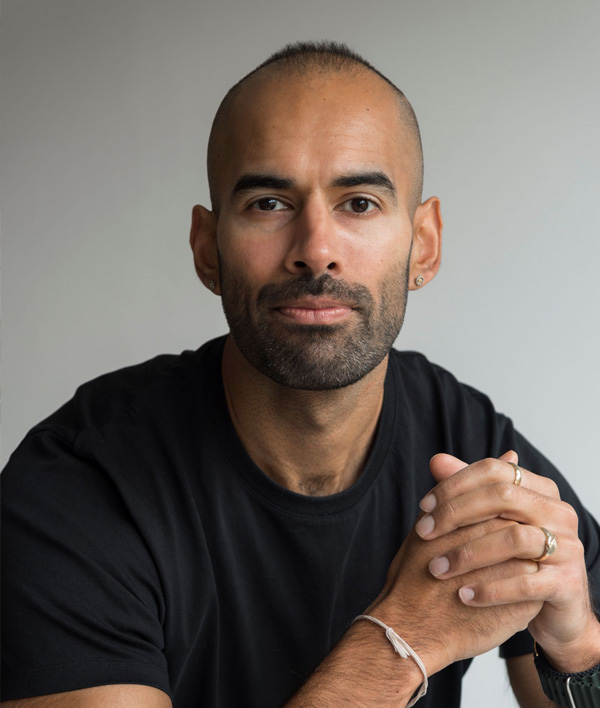

Karandeep describes himself as someone who takes on strange projects, and his career spans managing Special Vehicle Operations projects at Jaguar Land Rover, guiding Arrival as part of the early management team from a small start-up to a record-breaking IPO, and helping battery materials innovator Nexeon secure $170m in Series D funding. After holding a variety of C-Suite and directorial roles, he’s now entered the world of venture capital, helping to spin out the next wave of technology start-ups as Entrepreneur in Residence at Oxford Science Enterprises, whilst also pursuing the founding of his own startup.

Personable and friendly, he wears his formidable expertise lightly, but his track record in automotive design and engineering, commercialising new technologies and building successful teams speaks volumes. We sat down with him to explore the different stages of business he’s experienced, what it takes to succeed in each - and what motivates him personally.

Thanks for speaking to us, Karandeep! Your career arc takes us nicely through different sizes of organisation - but in reverse - so talk us through those career moves and how you came to experience organisations as such different stages of growth. Was that planned, or did it evolve organically?

My pleasure! And that’s true, my career has taken me from a large institution - Jaguar Land Rover - to a company of one. My career moves resulted in a steady change in both the kind of company and the size of company I worked in. I suppose I’ve been moving towards smaller companies, at an increasingly early stage of development.

I joined JLR after it had been acquired from Ford by Tata, so it was a company of over 35,000 employees. I got hired as part of an undergraduate scheme. I was lucky to get in; it gave me a safety net and was a great way to start a career and create strong foundations.

There were approximately 15 of us in my scheme. When you’re in an organisation that big, you can have a very different experience from one person to the next. Mine was good. I worked in a part of the organisation that was spearheading design and features of vehicles, so it was inspiring - I was in the design department.

Our working strapline was, “we’re a design-led business”. We were making design statements and other teams got behind us and tried to deliver things that customers love as soon as they see it. I worked with production engineering, supply chain and procurement. I saw how vehicles came together in practice, and I had the safety net to fail. I didn’t know what I didn’t know, and I failed faster than I recognised. That gave me confidence that things not working are a natural part of progress, which I’ve carried ever since.

I got to work for Special Vehicle Operations at JLR, which existed to do the “cool” or niche stuff — projects for ultra-high-net-worth customers, bespoke colours, custom interiors, even stunt and one-of-a-kind cars for movies like Spectre. We were moving away from an industrialised process into something so bespoke you couldn’t build it by following standard protocols.

That experience gave me a mindset: cut down processes, identify the minimum testing and validation required, and ask whether that can be standardised or whether the design and production is a case-by-case scenario. The mandatory layers of signoff, with designs taking 24–36 months, started to feel limiting. I wanted to create faster, cheaper mechanisms, and as it turned out, Arrival was the place where I’d get to test that.

That’s quite a shift. How did it happen?

After delivering a few projects at JLR, I saw many of my friends heading to California, where startup EVs like Canoo, Lucid and Faraday Future were appearing, and Tesla was spearheading change. I wanted a piece of it. I quit JLR without a job to go to – I just wanted to tour and see what I could find.

I realised quickly that people liked my energy, but I wasn’t senior enough to qualify for a special talent visa — I had to go through the lottery, and I didn’t get it. Then a friend introduced me to Arrival - which at the time was called Charge Automotive - based here in the UK. It was a tiny company, with CAD laptops on the workshop floor next to the vehicles. At JLR the core teams could be tens of miles away from where the cars were made, so going from that environment to one where I could see the vehicles being built in front of me seemed amazing and gave me lots to get my teeth into.

Critically for me, there were no established processes, it was just blank sheets and big questions everywhere; the main question was “How do you electrify commercial vehicles, cheaply and quickly?” I fell in love with that mission. When I started, I was employee number 51. There was no marketing department to call for customer insight, no validation process to test a part, we had to stitch all of it together; I was thrown in at the deep end.

Startups like Arrival (at the time) and established OEMs like JLR are two obvious extremes: how sharply do they contrast in the day to day?

In large organisations, everything is defined by templates: “we’ll make this product, with these features, and that defines a generic timeframe.” It’s efficient in its own way, with safety nets and historical backtracking. But it can feel repetitive and very process-led, it isn’t built for speed or need. Startups are nimble, creative and fluid. You can deliver something minimal and improve it, however it isn’t a robust or efficient way to run a business as you grow. But it depends which stage you join at, and there’s heartache too. You need resilience because you can be sideswiped by decisions, sometimes several times a day.

Let’s talk about the stage between the two: after spending time at Arrival you moved on to Nexeon, a battery materials scale-up. What was that environment like?

Scaleups, like Nexeon, are a mix. You have the product and you know it well, but now it’s about making tonnes of it. You want to act like a startup, but you’re dealing with processes designed for 10,000-person organisations. It can be challenging to move as quickly as you’d like to, and there can be a mix of attitudes: some people resist change, others push for it, and the whole company has to adjust.

At Nexeon I was driving that change, implementing processes quickly while trying not to stifle the culture. I was the youngest member of the executive team, hired to bring energy and be a pivot point as the company shifted from defining the material to getting it into customers’ hands. My startup mentality was occasionally at odds with colleagues from process-driven chemical manufacturing. I had to learn resilience, and to respect that not everyone sees things the same way.

Automotive is regulated, but chemicals are even more so, albeit nowhere near as complex. I hired someone who is an operator to her core to help me with process implementation, and even she told me: “you can’t not follow your own process!” That was a learning moment. I also helped build out the executive team alongside the CEO and CFO — new COO, CCO, CTO, VP of Engineering — as well as my own teams.

And now you’re back at the very beginning, with Oxford Science Enterprises…stealth mode?

Yes - I’m going all the way back to stealth mode, pre-startup! I left Nexeon to join Oxford Science Enterprises as an Entrepreneur-in-Residence. The programme partners people like me with academics to spin out companies from the Oxford ecosystem.

That sounds really exciting - how did that happen?

After my time at Nexeon I was asking myself: do I go back into automotive, into batteries, or do I start something new? It was a chance to pause, and this felt like a good way to embark on the journey. You get VC support and learn how investment works. They take on two or three people a year, and when I got the offer I thought, “go for it now”.

I’m now on the verge of spinning out my own company. I’ve worked with people from investment and consultancy backgrounds, learning the nitty gritty of how to create financial projections, business plans, and how venture-building works. These aren’t things you always learn in my historical roles in industry, but they matter to both customers and investors.

OSE has been running the programme for a few years. There are thousands of people in the Oxford network, and I’ve spoken to some amazing, super-smart people. The project is a bit like speed-dating in how you are matched up to innovators and choose who you work with. You have to think, “can I work with this person for seven-to-ten years?” That’s the mindset. It makes finding the right person harder, but it’s an essential question. I’ve met lots of investors and academics, and I’m close to taking one opportunity to our investment committee for seed investment.

In a situation like yours at OSE, what draws you in the most - the person or the technology?

I pick the great person. You can shape the idea with a great person, and that creates a better opportunity. Anyone that I don’t get on with, or might not take a liking to me, can find plenty of other people in the network where they’ll have a better connection; if you force the relationship just because you like the tech or research, you’ll end up doing it a disservice later down the line. If there’s someone I feel I can partner with, I’m confident I can help create the stepping stones and together we’ll make something great.

You’ve worked in so many different environments. What patterns do you see in your career that tell you where your strengths lie?

As I moved through jobs early in my career, I was often unsure what I was good at and always had imposter syndrome. But when I reflect, I’m always proud of the teams I’ve built. There are several amazing engineers who went on to brilliant roles, and I love seeing that. So I think I’m pretty good at bringing people together and creating cracking teams.

I’m not the biggest fan of LinkedIn ‘influencers’ or ‘productivity gurus’, but I was scrolling and saw something on LinkedIn that just lodged in my brain. It was about how important it is to find your “currency” — what people would pay you for or want your time for. Do what you enjoy but maximise what you’re good at. I enjoy tennis, but I know I’ll never make it to Wimbledon! So you need to maximise your skills, get paid for it, and then you can enjoy your passions, your family or whatever you want to.

What motivates you in your work?

I love building and delivering things! I’m also really driven by the democratisation of technology. It annoys me that I have the ability to buy the latest iPhone every time one is released, but someone living on the same street might not be able to. I’d like to help deliver technology that helps level the playing field for as many people as possible.

The latest technology disparity isn’t the only issue. Advanced tech gives access to the internet, to new information, to new services. It’s not just about a new phone – it’s about disparities being compounded again and again. I’ve always liked to work on technology that could help democratise things for people.

Technology is your window to everything now. My parents are as capable as me, but how easy or not it is to interact with technology changes your perception of your capability. Access to information in a form that suits people, in a way they can absorb it, means we can make good decisions about our lives and the things we need. Product, service and experience designers are a fundamental part of helping with that — refining features, providing information in a way that lands best; I love working with teams that can design and engineer for the whole end-to-end experience

Thank you Karandeep

Thank you - it was fun reflecting back on my career so far!

A huge thank you to Karandeep for sharing his time and insights with us for this blog; it was a real pleasure.

Insights

When your employer brand speaks for itself: a case study of Magma Global

Josh Richardson joined Magma Global in 2014 after completing a Master’s Degree in Mechanical Engineering. He now leads the Design and Test Department, specialising in the mechanical testing of composite structures

Ten years and £15,000: an American engineer’s journey to settling in the UK

Sophia Heath is a friend to Gerrell & Hard, a talented STEM professional and one of a group of successful Junior Product Engineers Gerrell & Hard placed at Polestar in 2021.

Paul Mackenzie: a journey through composites engineering, luxury and leadership

A legend within our industries, Paul Mackenzie has transitioned seamlessly across automotive, luxury marine and now into the world of luxury collectables with Amalgam Collection.

Subscribe to our LinkedIn Newsletter, TechTalent, for news and opinions from the frontline of tech recruitment.